#354: Bitcoin NFTs Are Taking Off, & More

1. Bitcoin NFTs Are Taking Off

With the launch of the Ordinals protocol, the Bitcoin network can now support non-fungible tokens (NFTs)1 directly on-chain. Users can inscribe images and other data in satoshis, the lowest denomination of bitcoin.

Thanks to two Bitcoin software upgrades—Segwit in 2017 and Taproot in 2021—the Bitcoin network can incorporate novel metadata on the blockchain. SegWit expanded Bitcoin’s block size from 1 megabyte to 4 megabytes, and Taproot increased data limits, enabling developers and users to encode various data types.

To understand Bitcoin Ordinals, consider the analogy to the dollar: just as 100 pennies constitute $1, 100 million satoshis constitute 1 bitcoin. Similarly, just as one might engrave a design onto a penny, bitcoin owners can “etch” satoshis, thanks to BTC Ordinals.

To date, users have created more than 100,000 Ordinals on the Bitcoin blockchain, some of them commanding large premiums. Ordinal Punks, a spin-off project from the groundbreaking Ethereum-based CryptoPunks NFT collection, sold for 9.5 BTC, or ~$218,000. The Ordinals project has sparked intense debate in the Bitcoin community. Bitcoin “purists” oppose it, claiming not only that ordinal inscriptions are congesting block space at the expense of valid financial transactions but that they also put bitcoin’s fungibility at risk because certain satoshis are worth more than others. In contrast, Ordinal supporters maintain that inscriptions are boosting demand for block space and generating fees, compensating miners for securing the network. They also cite libertarian, free market principles, noting that the market should determine the optimal use of block space. In response to concerns about bitcoin’s fungibility, advocates liken Ordinals to “coin collections” and note that the market for collectible coins has not impacted the dollar’s fungibility.

In our view, Ordinals have activated a new wave of Bitcoin users and developers—a net positive. Enabling new types of innovation, Ordinals have rejuvenated developer interest in building Bitcoin infrastructure. During the next few months, wallets and marketplaces are likely to support Ordinals, broadening the range of Bitcoin use cases.

2. AI Is Edging Toward Human-Level Social Fluency

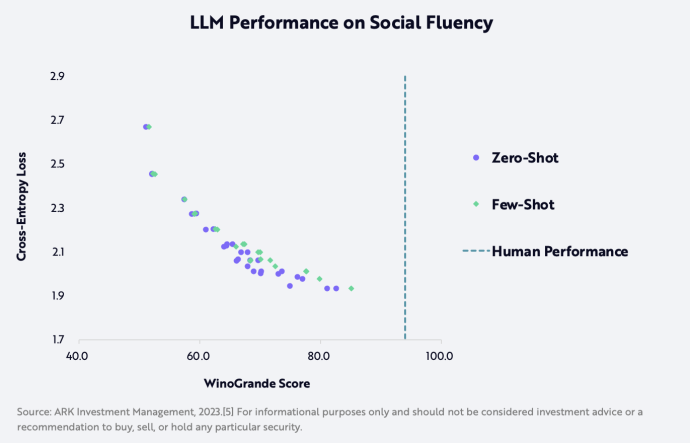

Anecdotal accounts of OpenAI’s ChatGPT highlight the human-level fluency of large language models (LLMs). The evolution of Artificial Intelligence (AI) fluency also can be quantified using dense, decoder-only LLMs’ performance on WinoGrande, a widely used benchmark that examines a model’s ability to demonstrate physical and social common sense. Plotting the WinoGrande evaluations of notable LLMs against their respective cross-entropy losses2 surfaces a power law relationship,3 as shown below. We believe that the human performance of 94 serves as an updated Turing Test4 for state-of-the-art LLMs, and as larger models trained on larger training datasets soon saturate this benchmark, we wonder what LLM use cases with human-level fluency will deliver, regardless of model accuracy.

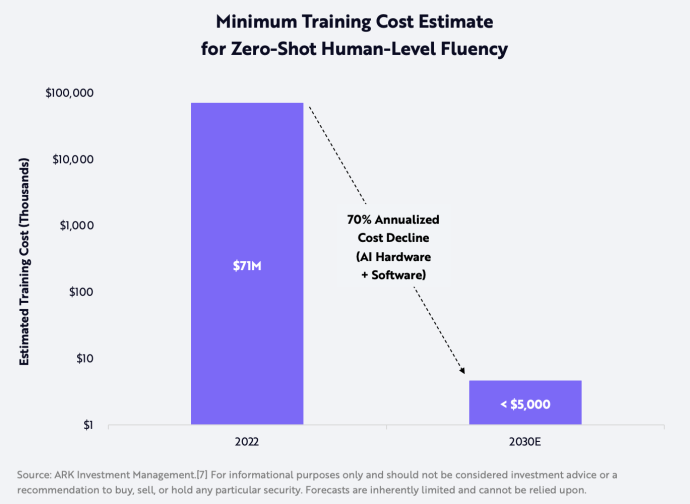

To train a dense LLM to deliver human-level performance on the WinoGrande benchmark under zero-shot6 evaluation, we hypothesize that the minimum total training cost today would exceed $70 million. ARK research, led by Frank Downing and William Summerlin, postulates that AI hardware and software costs are dropping at a rate of ~70% per year, suggesting that the training cost will drop from $70 million today to ~$5,000 in 2030. Embedded in consumer-facing platforms, such models could impact digital entertainment profoundly, creating new markets for AI companionship and enhancing existing markets for intelligent characters in video games.

[1] NFTs are unique digital assets that are cryptographically verifiable on a public blockchain. [2] Cross-entropy loss refers to the difference between a language model’s predicted probability distribution over the next token in a sequence and the true distribution of the next token. [3] A power law relationship refers to a relationship between two variables where one variable is proportional to a power of the other variable. [4] Proposed by Alan Turing, the Turing Test is a measure of a machine’s ability to exhibit intelligent behavior indistinguishable from that of a human. [5] See references 1-15. [6] Under zero-shot benchmark evaluation, the model is tested on new task categories for which it has not seen any examples during training, allowing one to assess the model’s ability to effectively generalize its learnings to new tasks. Under few-shot benchmark evaluation, the model is tested on new task categories for which it has seen only a few examples during training, allowing one to assess the model’s ability to learn from limited data and quickly adapt to new tasks.

3. Multivalent Sequencing Chemistry Should Democratize Access To Low Sequencing Costs

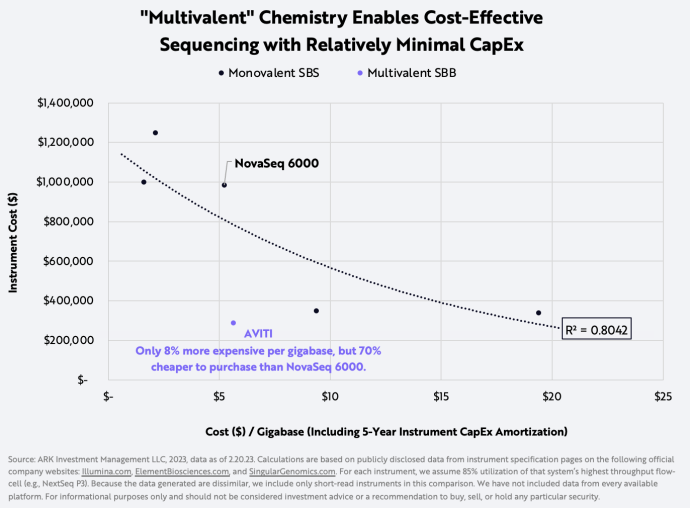

Since next-generation sequencing (NGS) debuted in 2007, the cost to sequence a human genome using short-read technology has dropped from $10 million to less than $200. That said, the sequencers generating the least expensive data often require large upfront capital investments. Although Illumina’s (ILMN) new flagship instrument, NovaSeq X Plus, can analyze a human genome for roughly $200, its $1.25 million capital cost makes it the most expensive instrument in genomic history. We show the relationship between the costs of data generation and NGS machines using short-read sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) technology in the chart below.8

Now, a private company, Element Biosciences, is using a novel sequencing chemistry called multivalent sequencing-by-binding (SBB)9 and lowering upfront costs. Element’s first instrument, the AVITI system, generates data almost as inexpensively as Illumina’s flagship system, the NovaSeq 6000, at a capital cost 70% lower.

Based on our research, SBB chemistry generates data more accurately than SBS. Element uses multivalent biochemistry, a clever technique that generates high-quality data at a fraction of the cost compared to traditional reagents. While myriad innovations underpin Element’s cost profile, multivalent reagents seem to be chief among them.

In addition to lower data costs, faster batching is another advantage of the AVITI system. Conventional high-throughput sequencers like NovaSeq require labs to batch dozens of samples prior to a sequencing run, prolonging turnaround times. Underutilized machines increase the cost of data generation, hurting the economics of labs. Because the AVITI system lowers the throughput necessary, sequencing labs can balance instrument utilization and turnaround times while generating data at near-industry-leading costs.

[7] See references 1-3. [8] Monovalent sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) refers to a type of short-read NGS chemistry wherein single, dual-modified nucleotides (including a blocking group and fluorophore) are added to a growing template DNA strand in cycles. Multivalent sequencing-by-binding (SBB) refers to a type of short-read NGS chemistry wherein nucleotide conjugates containing multiple fluorophores are contacted, and then incorporated, into a growing template DNA strand in two-step cycles. [9] Sequencing-by-binding (SBB) refers broadly to a type of short-read NGS chemistry wherein the interrogation and incorporation steps are distinct rather than combined, as is the case with SBS.